Wool warms when wet

Oct 17, 2024

Wool warms when wet. The first time I heard that phrase I didn’t believe it. Even though I was wearing a sweat soaked cotton sweatshirt and sweatpants in a snowstorm after my Walls coveralls were too warm (Walls workwear is underrated in my opinion). An old hat, wearing what looked like a Mackinaw Cruiser, saw my teeth chattering and told me that wool was definitely the way to go. I heard it, but I didn’t listen. How could wool keep warm when wet, everything is cold when wet. If it really did, scuba divers would wear a sweater instead of a wetsuit. I thought I was right, so stubbornly, I kept freezing for the rest of the all-night job shoveling snow.

I wasn’t that big into materials or fabrics at that time. I just thought wool was scratchy, hard to wash, and expensive for the sake of being expensive. Therefore, I never really considered it as an option for me as a college student. That is until I met one crunchy guy at college who never wore shoes (I once saw this guy walk through a native prairie barefoot and then, unfazed, stepped on a prickly pear cactus). The closest thing he got to shoes were wool socks with a leather outsole, only to be worn in the coldest parts of northern Iowa winters (like lose a toe kind of cold). Even at the coldest, he wasn’t shy about walking through snow, which I assumed got wet after the snow melted under his body heat, but he didn’t share my worries. He then shared that wool insulates when wet and I told him I didn’t believe it. We then had a very long winding and convoluted conversation that can easily be summarized by two points 1) wool doesn’t absorb water while 2) readily adsorbing vapor.

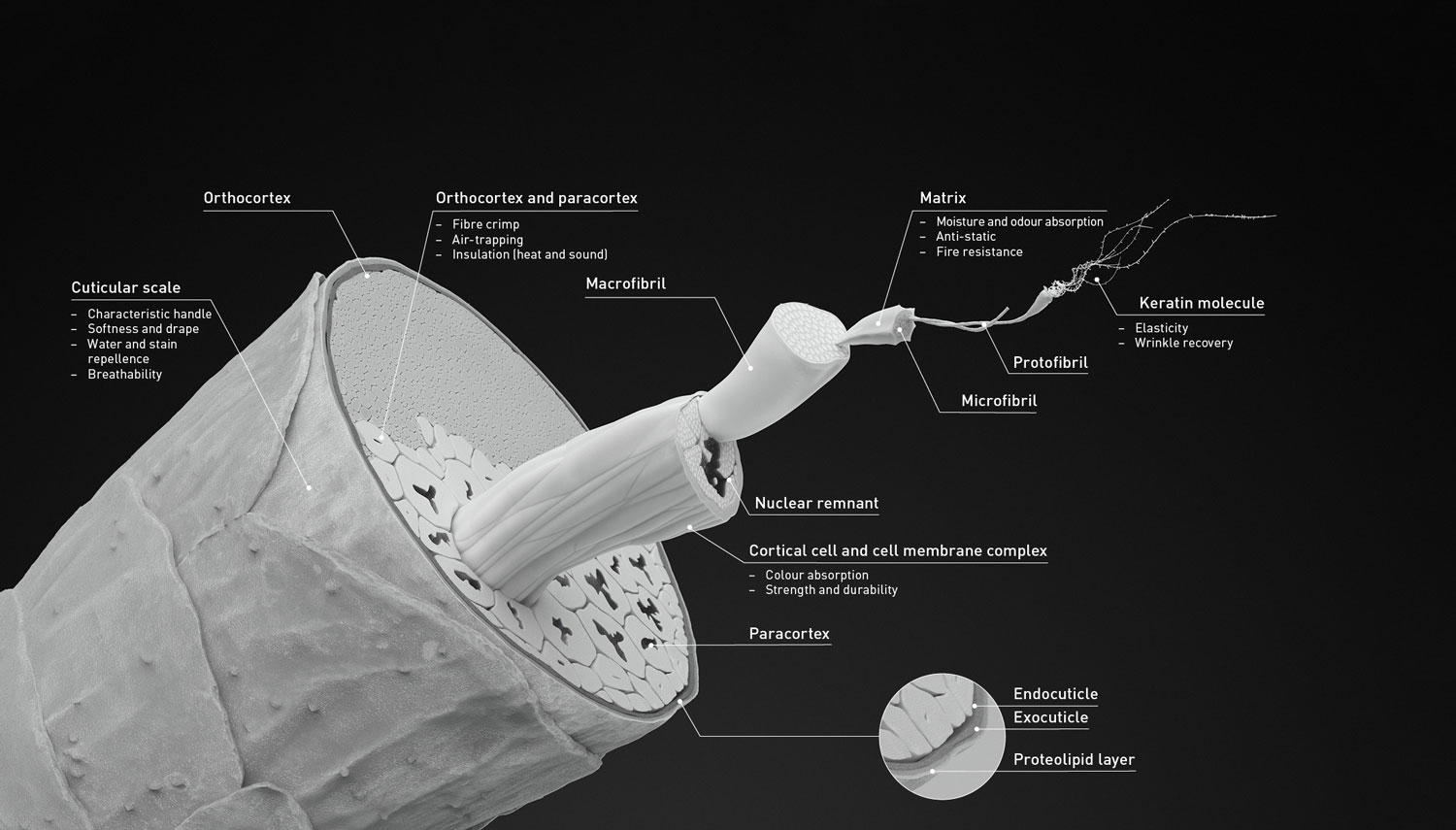

Reason number 1 may not be as exciting as the second (foreshadowing). However, the wool fiber’s inherent structure, and presence of lanolin, underlies possibly the major reason for its wet warmth. Simply put, the wool fiber has the inner cortex (made of many subtypes, see below) and the exterior cuticle that is made up of small scales with little to no gap between them. The cuticle acts as a barrier to the cortex so any water that comes in contact with it is shed off like shingles on a roof. Further, a natural oil called lanolin, secreted from sheep’s skin, gets trapped/coats the exterior wool fiber. which prevents water even getting to the cuticle, let alone the cortex, together culminating in a water-resistant fiber.

But how does this help with warmth when wet? I will tell you. When wool is completely soaked/submerged, and then removed from water, the water-resistant properties quickly drain the fabric to where the external cuticle of the fiber is dry to the touch. When dry, wool can then continue its normal insulation properties like low conductivity of heat (feels warm to the touch) and ability to trap air (forming pockets of air that buffers the temperature) to keep you nice and cozy wozy.

The second reason, the one I find the coolest, is adsorption, also known as sorption. Yes I spelled those words correctly. Adsorption is a process where molecules bind to the surface of a material (in this case water vapor binding the surface of wools internal cortex fibers) as compared to absorption where molecules are drawn into another material (like water into a paper towel). Most materials have the ability for adsorption, even cotton, but wool can adsorb approximately 35 percent of its weight in vapor (Stuart, I. M and Schneider A, M 1989; Holcombe B. 2009).

That all sounds fine and dandy, but how does that make you feel warmer? Well you see, when wool adsorbs vapor, the water molecules bind to the outer surfaces of the cortex fibers, and release energy in the form of heat. That’s right, it actually gets warmer. There are reports that some types of wool can release enough heat to be compared to a heated blanket, where specifically, one kilogram of dry wool can release same amount of heat energy as an electric blanket running for eight hours (Stuart, I. M and Schneider A, M 1989; Holcombe B. 2009).

Though most fabrics have adsorption, wool is one of the best at releasing heat. Further, the above-mentioned water-resistant capabilities prevent having excess water on the outside of the fiber making the loss of energy through evaporation (that requires heat energy) less likely. An example of how evaporation can sap heat is what occurs in cotton where cotton does release energy through adsorption, but the absorbance of water keeps excess water around that can readily evaporate pulling heat away making you feel colder. Hence cotton kills and wool warms.

This issue of the Proceedings of the Ferrous Mollusk is written by Zachary Wayne.

References

Image: https://www.woolmark.com/fibre/

– Stuart, I. M and Schneider A, M. Perception of the Heat of Sorption of Wool, June 1989, 324.

– B. Holcombe, Wool Performance apparel for sport, Advances in wool technology, Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2009, 272.